No one knows the struggle of living with toxic pollution like the people who face this challenge everyday. Environmental Health Coalition believes that those affected should have the opportunity to raise their own voices to demand change. That’s why much of our work takes place in low-income communities of color in the San Diego-Tijuana Region.

In these communities, among the poorest in the region, residents bear a disproportionate pollution burden, with record asthma hospitalization rates and long-term consequences like cancer and heart disease. Many residents are immigrants from Latin America, Asia and Africa, and many have little formal education.

Problems in these communities are common to many low-income communities of color: substandard housing, over-crowded schools, a lack of social services, low-paid jobs, polluting industries mixed with residential and commercial sites, industrial truck traffic, lack of parks and healthy food outlets, severe air pollution and lead contamination in aging housing stock.

On behalf of and with these low-income communities of color, we work at the local, regional, state, national and international levels to educate policy makers about opportunities that will accomplish our goals and benefit low-income communities. We share our models, learn from others, and promote environmental justice policies at every level of government.

There are no articles in this category. If subcategories display on this page, they may have articles.

Subcategories

Local

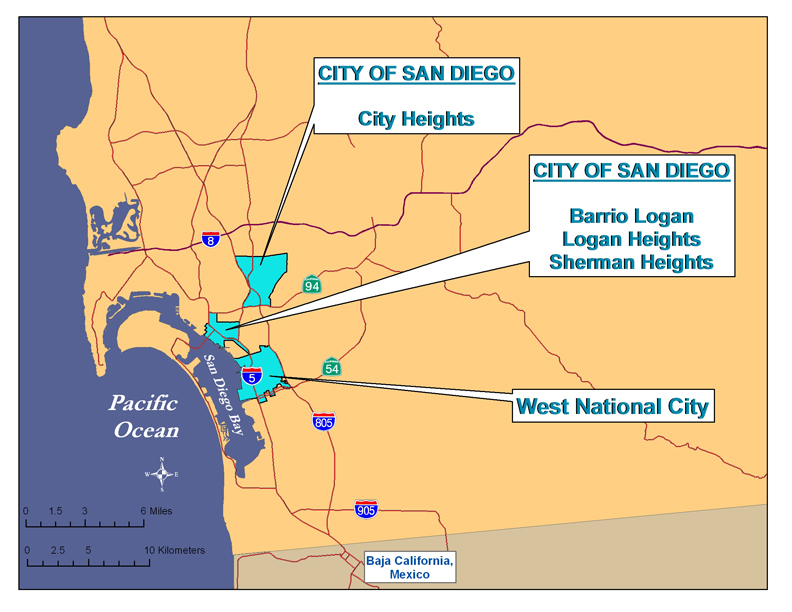

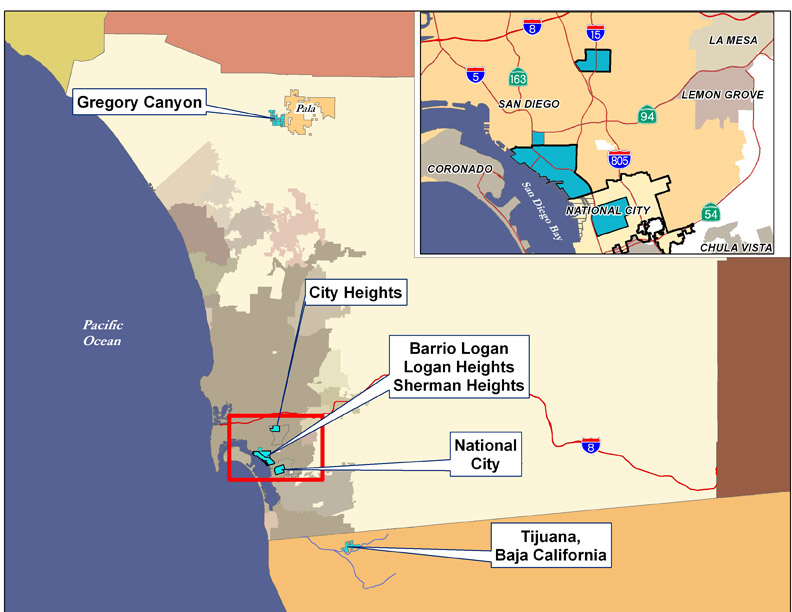

The majority of Environmental Health Coalition's work supports residents in low-income communities of color in urban areas of San Diego County and the communities around San Diego Bay. These are the largely Latino communities of Barrio Logan, Sherman/Logan Heights, and City Heights in the City of San Diego, and in National City with major emphasis on the Westside. These residents immigrated from Latin America, Asia and Africa, and many have little formal education.

Problems in these communities commonly occur in many low-income communities of color: substandard housing, over-crowded schools, a lack of social services, low-paying jobs, polluting industries mixed with residential and commercial sites, industrial truck traffic, lack of parks and healthy food outlets, severe air pollution and lead contamination in aging housing stock.

All of EHC's target communities developed around the same time in San Diego's history, the late 1860-80s, and went through similar transitions. Hopes of a railroad line connecting San Diego to points east rose and fell, and with these hopes land speculation was followed by financial crashes. Our region developed first what is now downtown San Diego, and by the late 1880s, the adjacent communities of Logan Heights (which then included Barrio Logan) and Sherman Heights got subdivided. Public transportation to these neighborhoods and out to City Heights allowed the population to grow. Logan Heights and Sherman Heights were upper class neighborhoods; City Heights was a working class neighborhood.

National City, San Diego County's second oldest city, developed around the same time, again driven by hopes of a railroad. It developed as an agricultural and industrial hub, with a population spanning the economic and ethnic spectrums.

Improved roads and the introduction of the automobile allowed many of the wealthier residents to move to new suburbs, and Logan Heights and Sherman Heights became home to successive waves of immigrants and minorities who were excluded from living in the new neighborhoods by racial, ethnic, and religious discrimination: Irish, Jews, Japanese, Chinese, African Americans, and Latinos. After World War II, National City became home to a large Filipino population. City Heights was the first home of many Southeast Asian refugees following the Vietnam War and home to many other more recent refugees following civil strife in their homelands.

Common factors that contributed to the decline of each neighborhood include:

Common factors that contributed to the decline of each neighborhood include:

- The construction of highways and freeways

- Increased population density

- Absentee landlords and the deterioration of the housing stock

- Increased industrialization

- Zoning changes

- Wars and the rise of San Diego as a military center

Place matters

According to research conducted by The California Endowment, one's zip code is a reliable predictor of life expectancy. A common thread in all of EHC's work is the recognition of the cumulative impacts of environmental, social, political and economic vulnerabilities that affect the quality of life in our target communities.

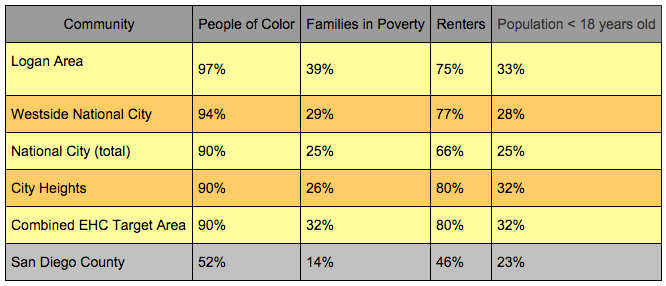

The following chart uses 2010 Census and American Community Survey (2009-2013) data to compare some of these factors in EHC target areas to the County of San Diego as a whole:

For more information on each of these neighborhoods, use the menu bar at the left.

Greater Logan Area

The "Historic Logan Heights" area includes the communities of Logan Heights, Barrio Logan, Memorial, Sherman Heights, Grant Hill, Stockton, Southcrest and Shelltown. Environmental Health Coalition works throughout this area, but especially in Barrio Logan, Logan Heights and Sherman Heights.

(insert map showing Historic Logan Heights communities with communities identified and major freeways)

History:

Historic Logan Heights is a microcosm of environmental racism in the United States. You can find it all here:

• A community of color created by racially discriminatory real estate covenants,

• Overcrowding, as more and more people are restricted to a small area,

• Encroachment of industry into residential areas,

• Effects of war and economic downturns on immigrant communities,

• Destructive effects of highways and bridges,

• Failure of government to provide services, provide protective zoning, and keep their promises, and ultimately

• The conversion of once vibrant communities into a land of junkyards, poverty, and substandard housing.

Much of this transformation took place from the 1920's to 1950's, but the community was physically torn apart in the 60's. In 1963, Interstate 5 was built through the middle of Logan Heights – the area to the northeast of the freeway retained the name of Logan Heights, while the area to the southwest became known as Barrio Logan. In 1967, the Coronado Bridge was built, dissecting the new area of Barrio Logan. Thousands of homes were destroyed and families displaced by these events.

But this period also sparked the birth of Barrio Logan. When land that was promised as a park under the bridge was instead slated to be turned into a CalTrans workyard, people revolted. Eventually Chicano Park was created and is now home to world famous murals, a free health clinic was established, many of the junkyards were eliminated, and in 1978 the Barrio Logan/Harbor 101 Community Plan was adopted.

Click here for a more detailed history of the area. (Link to Historical Resources Survey, Barrio Logan Community Plan Area)

For more information on each community and EHC's past and current work, click on the map or community name.

Demographics of Logan Area:

Environmental racism is not easily defined; it is the cumulative impacts of environmental, social, political and economic vulnerabilities that affect the quality of life of a community.

Insert chart for Barrio Logan, Logan Heights, Memorial, Sherman Heights, Grant Hill, Stockton, Southcrest, Shelltown: %people of color, %poverty, %children under 6 and 18, median age of housing, %immigrants, %Spanish spoken at home, %with high school degree of less

Pollution burden:

San Diego Regional

Environmental Health Coalition's efforts are mainly focused in communities but a glance at our history shows that we have been involved in many regional issues such as community right-to-know, hazardous waste cleanup and treatment, watershed protection, pesticide use reduction and pollution prevention policies, just to name a few.

Environmental Health Coalition's efforts are mainly focused in communities but a glance at our history shows that we have been involved in many regional issues such as community right-to-know, hazardous waste cleanup and treatment, watershed protection, pesticide use reduction and pollution prevention policies, just to name a few.

EHC's current regional issues include work on San Diego Bay, Port of San Diego activities, the Regional Transportation Plan, and Gregory Canyon Landfill.

Port of San Diego

The San Diego Unified Port District was created by state legislation in 1962 to promote commerce, navigation, recreation and fisheries for most of the tidelands in the five cities around San Diego Bay (San Diego, National City, Chula Vista, Imperial Beach and Coronado).

The San Diego Unified Port District was created by state legislation in 1962 to promote commerce, navigation, recreation and fisheries for most of the tidelands in the five cities around San Diego Bay (San Diego, National City, Chula Vista, Imperial Beach and Coronado).

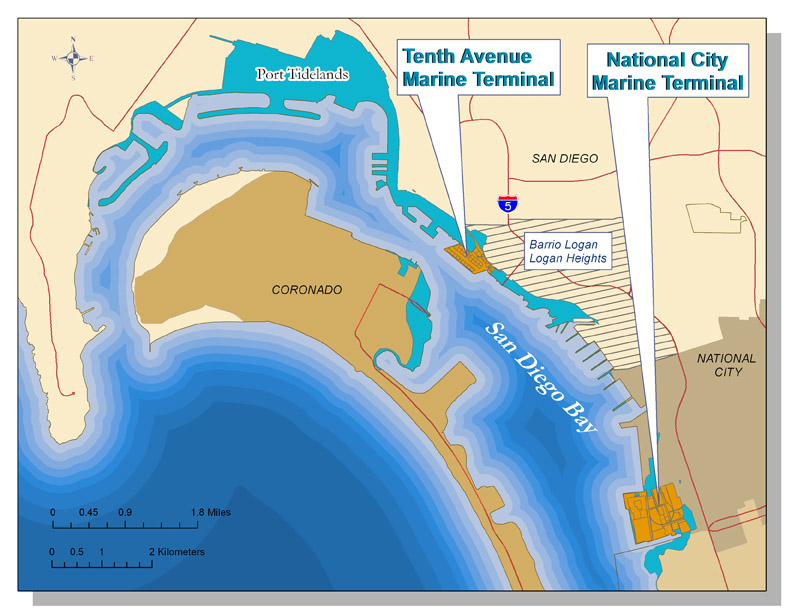

The Port has jurisdiction over 3,415 acres of land surrounding San Diego Bay. It is the landlord for 600 bayfront tenants, operates {tip The Port's two marine terminals::The National City Marine Terminal and the Tenth Avenue Marine Terminal in Barrio Logan}two marine terminals{/tip} and two cruise terminals, and maintains 17 parks.

Environmental Health Coalition has a long history of involvement with the Port District, from securing a ban on methyl bromide fumigation at the Tenth Avenue Marine Terminal to placing fish consumption warning signs at piers to helping it develop an Integrated Pest Management Plan for its parks and buildings.

EHC is a member of the Port's Environment Committee and the Climate and Energy Working Group. EHC also co-chairs the Wildlife Advisory Committee created as part of the Chula Vista Bayfront Master Plan settlement.

Recent and current efforts with the Port District include

Chula Vista Bayfront Master Plan and Wildlife Advisory Committee

Climate Mitigation and Action Plan

Sediment Cleanup in San Diego Bay: Several current and former Port tenants have been named as dischargers in a Cleanup and Abatement Order issued by the San Diego Regional Water Quality Control Board. These are National Steel and Shipbuilding Company (NASSCO), BAE Systems San Diego Ship Repair, Inc. (formerly Southwest Marine, Inc.), and Campbell Industries, Inc. The Regional Board reserved the right to add the Port as a discharger in the future if any of its tenants fail to comply with the order.) According to the draft 2012 CAO, the Port is now considered a discharger.

San Diego Bay

Environmental Health Coalition's Clean Bay Campaign began in 1987 with the goal to clean up, restore, and protect San Diego Bay as a clean and healthy multi-use water resource. Due in part to our strong advocacy and education efforts, regulatory agencies, elected officials, other non-profit organizations and the general population have since embraced this goal. EHC is reducing its efforts around San Diego Bay and will focus future attention to the Bay tidelands in our target communities of Barrio Logan and National City, and the completion of the following ongoing activities:

Chula Vista Bayfront Master Plan

History of San Diego Bay

History of San Diego Bay

Prior to the 1900s, San Diego Bay was a fertile, shallow bay supporting tremendous biodiversity in its open water, salt marshes and mud flats. The Bay changed dramatically. Navigation channels were dredged. Mudflats and salt marshes were filled. Commercial, recreational, industrial, and military installations now cover most of the bayfront, especially in the northern portion of the Bay. More than 90% of the mudflats and 78% of the salt marshes were eliminated and those that remain are found mostly in South San Diego Bay.

Millions of gallons of raw sewage were dumped into the Bay starting in the early 1900's, and by 1960 the Bay was in a continual state of quarantine. When the Point Loma Treatment Plant became operational in 1963 and the Bay started to recover from the effects of sewage pollution, evidence of its toxic pollution was unmasked.

While the Bay started to look good on postcards, years of neglect, inadequate enforcement, accidents, deliberate dumping and the urban development of thousands of acres upstream took their toll on the health of the Bay. In 1987, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration determined that the toxic pollution level in the bay was the sixth highest of 50 bays and estuaries across the nation. Later studies pinpointed the "toxic hotspots" around the industrialized bayfront adjacent to Barrio Logan.

The San Diego County Department of Environmental Health first documented human health risks from eating fish caught in San Diego Bay in a study published in 1990. Researchers found fish containing elevated levels of toxins like Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs), mercury and arsenic. They concluded that pregnant women and very young children could be at risk.

In 2005, Environmental Health Coalition conducted a survey of fishers on piers near areas of contaminated sediments. Of the 109 fishers interviewed, 96 percent were people of color. Almost two-thirds of the fishers eat their catch and 41 percent said they regularly feed the fish to their children. Recent visits to the fishing piers confirm that little has changed. Families are still using the bay as a source for food.

There are 22 different agencies with varying responsibilities for the water quality San Diego Bay, but the San Diego Regional Water Quality Control Board (RWQCB), the San Diego Unified Port District, and the U.S. Military have greatest responsibility.

The Port was created by state legislation in 1962 to promote commerce, navigation, recreation and fisheries for most of the tidelands in the five cities around the Bay (San Diego, National City, Chula Vista, Imperial Beach and Coronado). It is the landlord for the bayfront tenants and operates two marine terminals and two cruise terminals.

The RWQCB enforces both State and Federal Clean Water laws.

The Military presence in San Diego Bay began in 1919 and greatly expanded during and after World War II. It currently controls approximately 20% of the tidelands, including the largest naval base on the West Coat, the 32nd Street Naval Base.

Relationships to other EHC Efforts

South San Diego Bay

EHC's current efforts in South San Diego

Community Planning – insure that the Bayfront Master Plan is implemented

Green Energy/Green Jobs – make certain that the bayfront development utilizes the maximum renewable energy and the highest green building standards

History

Prior to the 1900s, San Diego Bay was a fertile, shallow bay supporting great biodiversity in its open water, salt marshes and mud flats. Dredging and filling of the Bay, along with development have eliminated over 90% of the mudflats and 78% of the salt marshes. Those that remain are found mostly in South San Diego Bay.

Most of the land surrounding San Diego Bay is controlled by the San Diego Unified Port District or the U.S. military. The last remaining piece of privately owned bayfront property was 125 acres between the Sweetwater Marsh Unit of the San Diego National Wildlife Refuge and a marina/commercial development on Port controlled land to the South. When developers proposed dense commercial and residential development at this site, environmentalists and South Bay residents objected.

Most of the land surrounding San Diego Bay is controlled by the San Diego Unified Port District or the U.S. military. The last remaining piece of privately owned bayfront property was 125 acres between the Sweetwater Marsh Unit of the San Diego National Wildlife Refuge and a marina/commercial development on Port controlled land to the South. When developers proposed dense commercial and residential development at this site, environmentalists and South Bay residents objected.

Sweetwater Marsh Unit of SDNWR

In the late 1970s/early 1980s two projects were proposed that would severely threaten these remaining wetlands habitats: a combined highway/flood control channel along the Sweetwater River that separates National City and Chula Vista, and construction of a 440-room hotel at Gunpowder Point along with high rise residential complexes on the D-Street Fill.

A multi-year legal battle, led by the Sierra Club and League for Coastal Protection, ensued. In 1987 a District Court judge issued a permanent injunction to stop all work, and in 1988 the 315.8-acre Sweetwater Marsh National Wildlife Refuge was created. It is now home to the Chula Vista Nature Center.

South San Diego Bay Unit of SDNWR: The water and land at the far south of the Bay was still unprotected

Pollution Burden

Pollution in South San Diego Bay has come from the South Bay Power Plant, bayside industries such as Rohr Industries, the nearby Interstate 5, and urban runoff.

Relationships to other EHC Efforts

Chula Vista Bayfront Master Plan

Although most of the land surrounding San Diego Bay is under the jurisdiction of public agencies, approximately 125 acres just south of the Sweetwater Marsh National Wildlife Refuge is privately owned.

There have been many proposals to develop this land, the most recent beginning in 2002. The City of Chula Vista gave Pacifica Development Cos. the right to develop the property and they submitted a plan for a high-density housing project called the Bayfront Villages. This proposal included 3,400 housing units in 20-story high rises.

Environmental Health Coalition's 10-year community organizing and advocacy efforts have led to the creation of a Chula Vista Bayfront Master Plan that protects the Sweetwater Marsh and greatly reduces the density of development. This will be accomplished through a land swap between the San Diego Port District and the City of Chula Vista.

Background

When Environmental Health Coalition learned of the proposed development, we immediately recognized that this high-density project didn't belong there and started our "Don't Pave Paradise" campaign. In December 2002, a special public meeting was called by the Chula Vista City Council. More than 400 people attended, universally opposing the project.

In January 2003, Pacifica revised its proposal (and changed the name to Bayfront Commons), reducing the number of units from 3,400 to 2,000. Still, this was the wrong proposal for such an environmentally sensitive location. Around same time, the Port was developing its Master Plan for the adjoining Port controlled property. The idea of a land swap between the Port and the Pacifica surfaced at the December hearing. This would allow the developer to construct housing on property further away from the Wildlife Refuge.

Community-driven land use planning

EHC used its community-driven land use model to develop a vision for the Chula Vista Bayfront. It formed a Chula Vista Community Action Team, provided the CAT members with education and resources to develop a vision, actively organized support for the vision, and developed an implementation and monitoring plan. Unlike EHC's other local community planning efforts, the Chula Vista bayfront currently doesn't have a residential section, so members of the CAT were drawn from other Chula Vista neighborhoods. The Bayfront Master Plan was seen as an opportunity to turn the area into a city-wide resource.

Step 1: Create the vision. EHC hired Doug Coe, the director of the San Diego State University Research Laboratory, to conduct a community survey to discover Chula Vistan's view on the development project. The results were released in April: an overwhelming majority of Chula Vista residents opposed high-density housing at the site and showed an overwhelming preference for low levels of development.

EHC's Chula Vista Community Action Team then developed its criteria for bayfront development:

- Protect wildlife

- Improve quality of life

- Employ sustainable development principles

- Be low density

- Create good jobs

- Include appropriate recreational opportunities

- Focus on transit, not roads

- Preserve the view of the Bay

- Protect air and water quality

- Use the natural beauty of the area as a focus

- Link to other regional development efforts (Port to south, national city to north, city core to east)

Step 2: Convert the vision into a land use map. The Community Action Team worked with a professional land-use planner to create a map reflecting their vision.

Step 3: Gain community support. From letter writing campaigns to house-to-house canvassing, EHC kept the community informed and involved in the process.

Step 4: Get the process started. In May 2003, EHC published a letter to the editor endorsing joint planning of City and Port for both pieces of property, and in March 2004 the Port, Chula Vista and Pacifica begin a joint planning process.

Step 5: Incorporate the vision into the elements of a new Community Plan. The City and Port established a Community Advisory Committee. The CAC supported a plan that closely reflected the vision developed by the Community Action Team.

Step 6: Gain support of local city council representatives. In March 2004 the Port, Chula Vista and Pacifica begin a joint planning process and in 2004 they approved the Community Advisory Committee's recommended plan.

Step 7: Be persistent. Although the plan was approved in 2004, the difficulties surrounding the land swap greatly slowed down implementation. In 2010, in order to facilitate implementation of the plan, a {tip coalition of environmental and community organizations::Environmental Health Coalition, San Diego Auduon Society, San Diego Coastkeeper, Coastal Environmental Rights Foundations, Southwest Wetlands Interpretative Association, The Surfrider Foundation-San Diego Chapter, and Empower San Diego}coalition of environmental and community organizations{/tip} entered into a settlement agreement with the Port and the City spelling out the conditions for the land swap and future development. These include buffer zones between wildlife areas and development, creation of the South Bay Wildlife Advisory Group to advise in the creation of the Natural Resource Management Plan, and minimum design elements to reduce pollution and energy consumption

Step 8: Coming Soon! Celebrate adoption, but monitor implementation. The Plan and Final Environmental Impact Report are currently being reviewed by the California Coastal Commission. Environmental Health Coalition is a member of the Wildlife Advisory Committee and will continue to monitor the project and its impacts.

Copies of the Chula Vista Master Plan and other documents can be found on the Port's website at http://www.portofsandiego.org/chula-vista-bayfront-master-plan.html

State of California / National

Environmental Health Coalition believes that the proper role of government is to protect human and environmental rights. In addition to working locally, we work at state and national levels to promote government policies and regulations that protect human health and the environment. Many of these efforts are in cooperation with our allies in the California Environmental Justice Alliance (CEJA).

Environmental Health Coalition believes that the proper role of government is to protect human and environmental rights. In addition to working locally, we work at state and national levels to promote government policies and regulations that protect human health and the environment. Many of these efforts are in cooperation with our allies in the California Environmental Justice Alliance (CEJA).

EHC's current efforts with CEJA include the California Energy Policy and Green Zones for Environmental and Economic Sustainability. These are far reaching initiatives that can benefit many environmental justice communities.

AB32, the California Global Warming Solutions Act passed by the California legislature in 2006, created an opportunity to put the state at the forefront of reducing greenhouse gas emissions. We have great potential for pollution reduction and a booming green energy economy. EHC and CEJA work to make certain low-income communities benefit from these policies.

The Green Zone initiative will create a federal designation for neighborhoods or clusters of neighborhoods that face the cumulative impacts of environment, social, political and economic vulnerability. Communities with Green Zone designations would be able to access benefits at state and federal levels. This would ensure that those communities most highly impacted by environmental hazards and economic stressors receive much needed resources and support.

President Barack Obama appointed our executive director, Diane Takvorian, as a member of the Joint Public Advisory Committee to the CEC. Through this membership, she hopes to strengthen the tri-national commitment to environmental justice and bring the voice of the people to the front and center.

While not a primary strategy, EHC will work with state and national legislators to develop and introduce specific legislation. Some examples include:

Military Environmental Responsibility Act

Lead Free Candy – State of California

More frequently, EHC works to influence policies and voter initiatives that have broad impact on our target communities.

California Environmental Justice Advisory Committee

Stop Prop 23

Baja California, Mexico

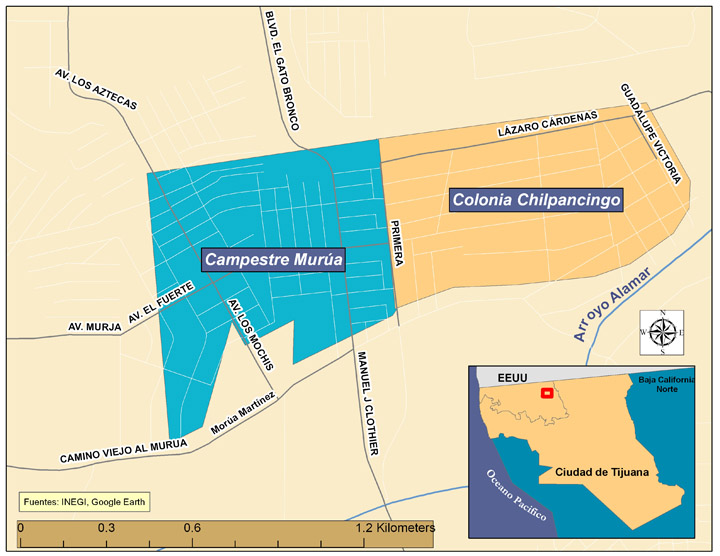

The communities of Colonia Chilpancingo, Colonia Murua and Nueva Esperanza share many of the problems found in San Diego's communities of color: substandard housing, over-crowded schools, a lack of social services, low-paid jobs, polluting industries mixed in with residential and commercial sites, industrial truck traffic, lack of parks and healthy food outlets, and severe air pollution. They are also adjacent to Tijuana's largest Maquiladora industrial complex.

EHC chose to work in these neighborhoods of Tijuana because their pollution problems skyrocketed after the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994 and the resulting growth of the maquiladora industry.

Although comprehensive economic and demographic data is not available for these neighborhoods, available data show that 67% of the homes have dirt floors, 66% do not have piped water, and 33% do not have sewer hook-ups. Two adults employed full-time in the maquiladora industry, the main source of employment, cover only two-thirds of the basic needs of a family of four.

President Barack Obama appointed our executive director, Diane Takvorian, as a member of the Joint Public Advisory Committee to the CEC. Through this membership, she hopes to strengthen the tri-national commitment to environmental justice and bring the voice of the people to the front and center. She is currently working to strengthen the Citizens' Petition process.

Email Updates

EHC News and Updates

- Video

This video commemorates Environmental Health Coalition's 40th anniversary. Founded in 1980, EHC builds grassroots campaigns to confront the unjust consequences of toxic pollution, discriminatory land use, and climate change.

Learn about our 40th anniversary celebration on August 20, 2020, including a full recording of the live event in English and Spanish, 40 years of EJ in pictures, and much more!

#40yearsofEJ