EHC's current efforts in Sherman Heights

EHC's current efforts in Sherman Heights

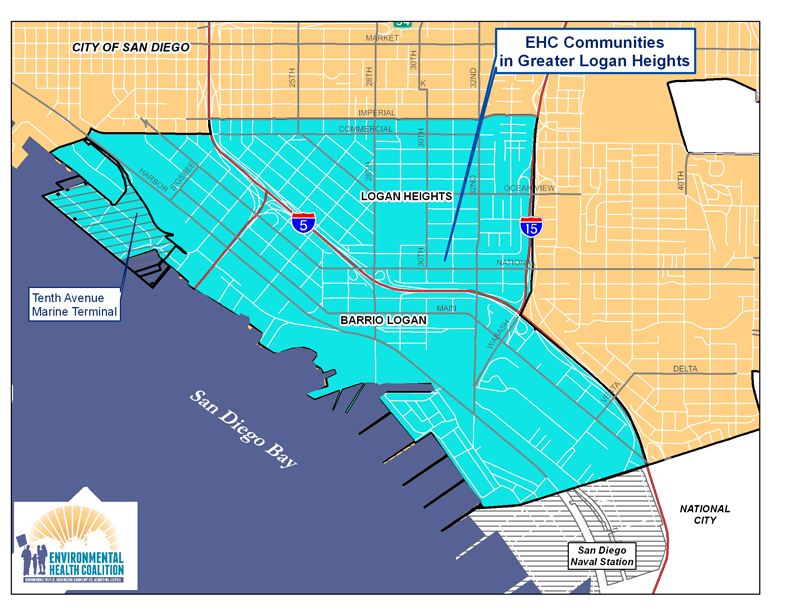

Community Planning – assist the Historic Logan neighborhoods of Sherman Heights, Grant Hill, Stockton, Logan Heights and Memorial develop a vision for the Commercial/Imperial Corridor as a vibrant community link

Healthy Kids – reduce lead poisoning and asthma associated with poor housing and air pollution

Green Energy/Green Jobs – improve the housing stock through energy efficiency and installation of solar energy and create green jobs for community residents

History

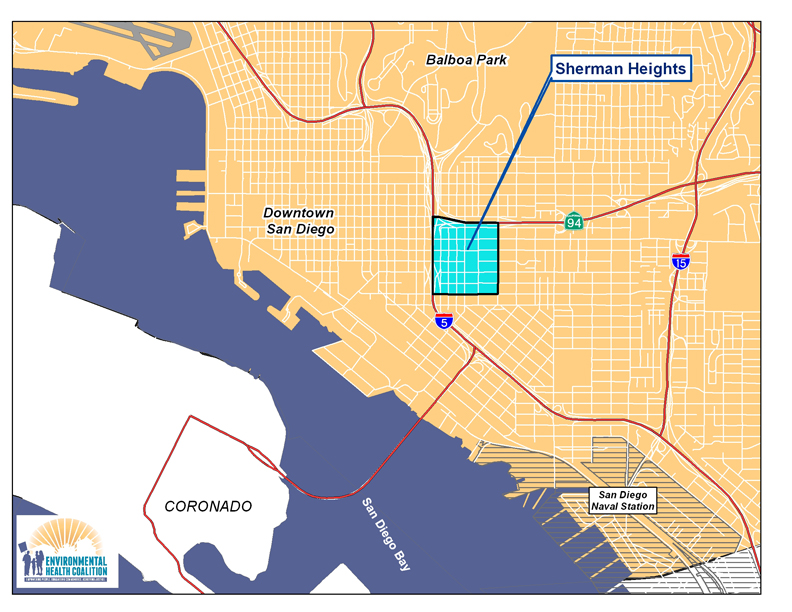

Sherman Heights is one of the oldest residential communities in the City of San Diego, being first subdivided in 1869. Its original boundaries went from Market Street to the north, 15th Street to the west, 25th Street to the east, and Commercial Street to the South.

The original settlers of Sherman Heights represented diverse economic groups, but as the wealthier residents left, Sherman Heights became home to racial, ethnic and religious groups restricted from the newer developments. In the early 1900's it was home to German, Irish and Jewish immigrants; in 1920s, it became home to Japanese and Chinese immigrants; through the 1940s it was a thriving middle class neighborhood.

Highway construction from the 1940's into the 1960's (State Route 94 and Interstate Highway 5) and the subsequent adoption of the 1987 Southeastern San Diego Community Plan redrew the boundaries. SR 94 became the northern boundary, I-5 the western boundary, and Imperial Avenue the southern boundary. The original 160 acres was reduced to about 140 acres.

Although much of the original housing stock remains, over the years many single-family homes were converted to apartments and second homes built in the rear yards. Home ownership declined and absentee landlords allowed the housing to deteriorate. Vacant land next to the freeways attracted criminal activity, and the 1970's and 80's were a bleak period.

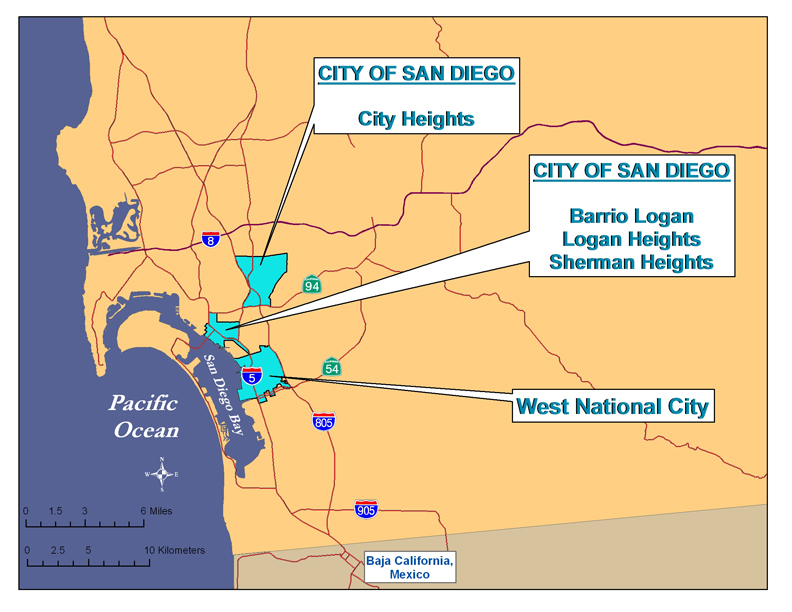

The Southeastern San Diego Community planning area originally included more than 7000 acres, including all of the communities recognized as part of the Historic Logan Area except for Barrio Logan. Because the planning area is so large, many of the communities have developed individual plans. The Sherman Heights Revitalization Plan was adopted in 1995, and included the commercial corridors along 26th Street to the east and Commercial Street to the south. The Commercial/Imperial Corridor connects the Sherman Heights, Grant Hill and Stockton communities to the Logan Heights and Memorial neighborhoods to the south. Imperial Avenue is mainly mixed-use commercial while Commercial is zoned industrial. A new Corridor Plan was initiated in 2011 to develop a new 20 year vision.

Environmental Racism

Environmental racism is not easily defined but easy to recognize; it is the cumulative impacts of environmental, social, political and economic vulnerabilities that affect the quality of life of a community.

Demographics

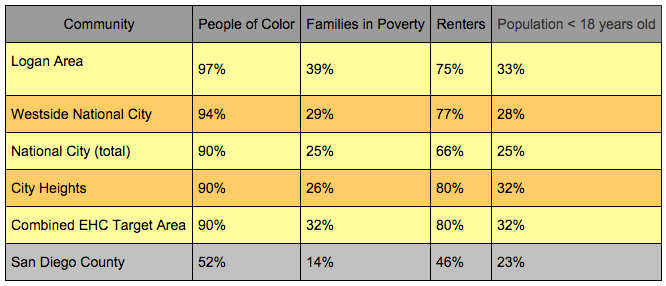

| Area | 2010 Population | Non-White | Under 18 | 18 and Older | Families in Poverty | Renter Households |

| Sherman Heights | 1,858 | 81% | 22% | 78% | 36% | 87% |

Pollution Burden

Sherman Heights is primarily a residential neighborhood, except for the Imperial/Commercial Corridor. Imperial Avenue is mostly commercial, while Commercial is light industrial. The pollution burden of Sherman Heights comes from the industries along Commercial Avenue, illegal auto-repair/body-repair shops in the residential area, its proximity to the freeways and the deteriorated quality of its housing.

EPA Respiratory Risk data from 2005 show that Sherman Heights residents experience a 5-6 times greater risk than a neighborhood considered "safe." Total cancer risk from air contaminants is among the highest in the County.

Sherman Heights has been identified as a "hot spot" for childhood lead poisoning due to the age and poor condition of its housing and the large number of children under the age of 6. Much of original housing was built in the early 1900's when levels of lead in paint were highest.

EHC's History/Successes in Sherman Heights

Read about EHC's City Heights Leadership Team and Community Action Team.

Common factors that contributed to the decline of each neighborhood include:

Common factors that contributed to the decline of each neighborhood include: