Versión en español a continuación.

Honoring Black Environmental Justice Leaders

The Intersection of Race and Environmental Justice

February is Black History Month, a nationwide observance to honor and celebrate the many contributions Black people have made to our nation and the world. In honor of this month, Environmental Health Coalition is celebrating black leaders in the environmental justice movement and our communities. To truly understand and appreciate these leaders, we must first acknowledge the tragic history of slavery, repression, and racism black people have endured in our country and still live with today.

The fight for environmental justice is the fight against environmental racism. It was the landmark report Toxic Waste and Race in the United States, published by the United Church of Christ in 1987, that documented the injustices endured by people of color, and especially African Americans. The report found that race is the most significant factor, more important than income, when locating toxic waste sites.

To this day, black communities continue to bear a disproportionate amount of pollution and its devastating health impacts. According to the American Lung Association, “Recent studies have looked at the mortality in the Medicaid population and found that those who live in predominately Black or African American communities suffered greater risk of premature death from particle pollution than those who live in communities that are predominately white.” As these studies make very clear, environmental justice fights for racial justice and the fight is not over.

Black leaders birthed the environmental justice movement and continue to be at the frontlines. We are honored to shine a light on just a few of these passionate and effective leaders who inspire us all.

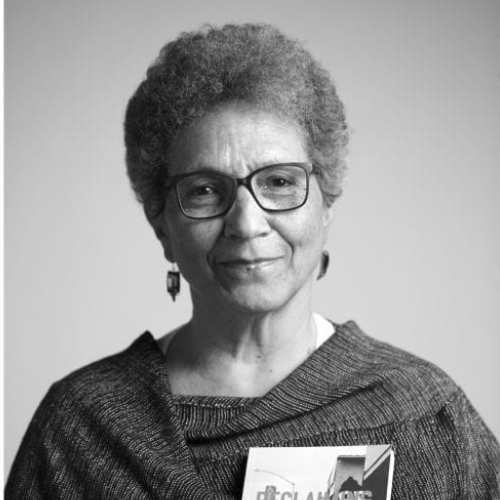

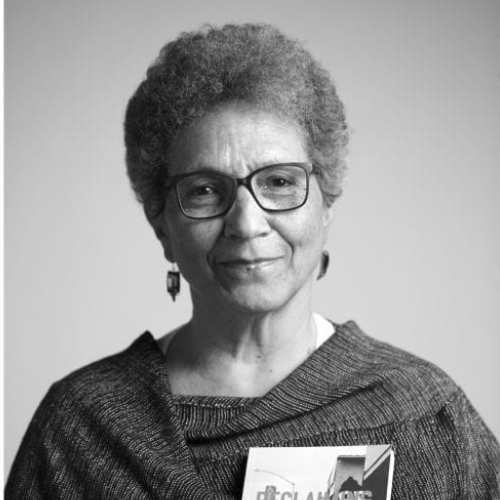

Vernice Miller-Travis

Environmental justice has been Vernice’s life work for more than thirty years. She is one of the nation’s most respected thought leaders on environmental justice and the interplay of civil rights and environmental policy. She was a contributing author to the landmark report “Toxic Waste and Race in the United States.” In 1991, she was a delegate to the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. At the Summit, she served on the small drafting committee that wrote the Principles of Environmental Justice. She is currently the Executive Vice President of the Metropolitan Group, a full-service strategic and creative agency dedicated to advancing social justice.

Environmental justice has been Vernice’s life work for more than thirty years. She is one of the nation’s most respected thought leaders on environmental justice and the interplay of civil rights and environmental policy. She was a contributing author to the landmark report “Toxic Waste and Race in the United States.” In 1991, she was a delegate to the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. At the Summit, she served on the small drafting committee that wrote the Principles of Environmental Justice. She is currently the Executive Vice President of the Metropolitan Group, a full-service strategic and creative agency dedicated to advancing social justice.

EHC had the opportunity to ask Vernice about the nexus between environmental justice and racial justice. She was kind enough to provide us with the below thoughtful response:

We understood from the earliest days of organizing and advocacy in our local communities that the environmental and public health threats we faced were rooted in systemic racism.

We started out fighting environmental racism. But, that framing made regulators at the local, county, state, and federal levels, as well as industry representatives very uncomfortable when we suggested that systemic racism was enmeshed in the land use, zoning, housing, and industrial agriculture and development patterns of decision-making. These decisions were grounded in historic practices of racial and ethnic segregation.

Long before the publication of Toxic Waste and Race, Race and the Incidence of Environmental Hazards, or Dumping in Dixie, every person of color living in the United States knew unequivocally that wherever we lived was profoundly different from where Whites lived, even if we lived in the same city, county, or town. Our schools and hospitals were different, our supermarkets and pharmacies were different, the housing stock, and recreational spaces were different. Transportation systems were different. When I say different, I mean profoundly unequal. But more importantly, the quality of the air we breathed and the water we drank was more often than not full of contaminants. This made us sicker and have shorter life expectancies.

The fight for Environmental Justice is now and has always been a fight for racial justice and equal treatment before the law.

Eric Wilson

Eric Wilson is Environmental Health Coalition’s Human Resources and Administration Director. Eric has more than 20 years of administrative and operational experience in for-profit and non-profit arenas. His heart is with social and environmental justice work. Through his leadership, Eric creates a collaborative and supportive working environment in which EHC staffers can develop into EJ champions and help residents realize their innate power to create healthy, pollution-free neighborhoods.

Eric Wilson is Environmental Health Coalition’s Human Resources and Administration Director. Eric has more than 20 years of administrative and operational experience in for-profit and non-profit arenas. His heart is with social and environmental justice work. Through his leadership, Eric creates a collaborative and supportive working environment in which EHC staffers can develop into EJ champions and help residents realize their innate power to create healthy, pollution-free neighborhoods.

Eric shared with us, “I am passionate about environmental and social justice because of an incident that happened to me when I was about 14. My brother-in-law was wrongly arrested and beaten very badly for driving in the wrong neighborhood. He was hospitalized for weeks. At this time, I found out what it meant to be black in the United States as my father had to explain the double standard to me. It angered me so much that I never forgot the experience and have since had a desire to fight for what is right. I hold true to Dr. King's quote:

‘Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.” “The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.’”

Roberta Alexander, PhD

A former black panther, Roberta has dedicated her life to social justice, education, and cultural enrichment. As a member of the Board of Directors since 2012, Roberta has helped guide Environmental Health Coalition through more than a decade of environmental justice challenges and success. She served as a faculty member in the San Diego Community College District for over 35 years. During her tenure, she was the Department Chair for English as a Second Language in Continuing Education at Centre City Adult School and the Department Chair of English at San Diego City College.

A former black panther, Roberta has dedicated her life to social justice, education, and cultural enrichment. As a member of the Board of Directors since 2012, Roberta has helped guide Environmental Health Coalition through more than a decade of environmental justice challenges and success. She served as a faculty member in the San Diego Community College District for over 35 years. During her tenure, she was the Department Chair for English as a Second Language in Continuing Education at Centre City Adult School and the Department Chair of English at San Diego City College.

Roberta shared with us, “In the 1960s, I lived in the flatlands of North Richmond next to the toxics-spewing Chevron refinery where it is no accident that Black and Brown folks are still the overwhelming majority of residents. Every single day, our children continue to struggle to breathe through the toxic fumes of neighborhoods like that one. Indeed, here in San Diego, nationally and internationally, air pollution, hazardous waste sites, lead poisoning, climate change, and water contamination disproportionately affect poor people of color.

George Floyd, when he was murdered by a knee on his neck, cried out, ‘I can't breathe.’ Our children use the same three words when they're struggling through an asthma attack.”

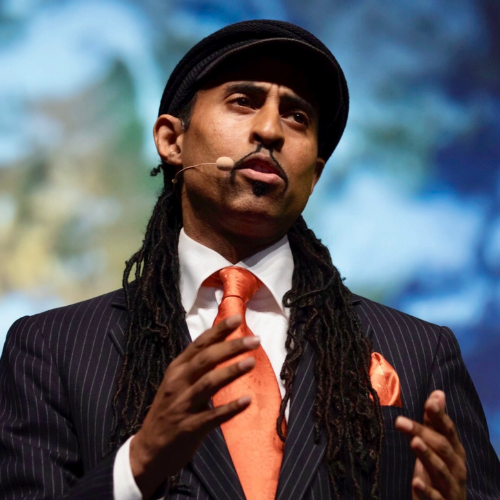

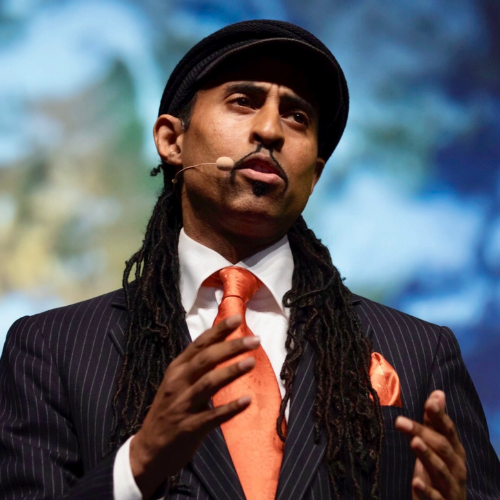

Mustafa Santiago Ali

Mustafa is a thought-leader and activist committed to fighting for environmental justice and economic equity. He worked at the U.S. Environment Protection Agency (EPA) for 24 years. At the EPA, he served as the Assistant Associate Administrator for Environmental Justice and Senior Advisor for Environmental Justice and Community Revitalization. During his tenure, he worked across federal agencies to strengthen environmental justice policies, programs, and initiatives. He also led the Interagency Working Group on Environmental Justice (EJIWG), which was comprised of 17 federal agencies and White House offices focused on implementing holistic strategies to address the issues facing vulnerable communities.In 2017, he resigned from the EPA to join the Hip Hop Caucus and lead their Environmental Justice and Community Revitalization portfolio.

Mustafa is a thought-leader and activist committed to fighting for environmental justice and economic equity. He worked at the U.S. Environment Protection Agency (EPA) for 24 years. At the EPA, he served as the Assistant Associate Administrator for Environmental Justice and Senior Advisor for Environmental Justice and Community Revitalization. During his tenure, he worked across federal agencies to strengthen environmental justice policies, programs, and initiatives. He also led the Interagency Working Group on Environmental Justice (EJIWG), which was comprised of 17 federal agencies and White House offices focused on implementing holistic strategies to address the issues facing vulnerable communities.In 2017, he resigned from the EPA to join the Hip Hop Caucus and lead their Environmental Justice and Community Revitalization portfolio.

For his lifetime of environmental justice work, EHC honored Mustafa with the Environmental Justice Champion Award in 2018. At the award ceremony, he gave a moving acceptance speech that is featured below:

Cecil Corbin-Mark

The environmental justice community endured a great loss when Harlem activist Cecil Corbin-Mark passed away on October 15, 2020. He was only 51 years old. Cecil was the Deputy Director and Director of Policy Initiatives at WE ACT, a West Harlem non-profit whose mission is to build healthy communities by ensuring that low-income communities of color participate meaningfully in the creation of environmental health and protection policies. Over his 26-year career at WE ACT, he helped develop and pass numerous bills in New York City and New York State, and managed WE ACT’s Washington, DC federal policy office.

The environmental justice community endured a great loss when Harlem activist Cecil Corbin-Mark passed away on October 15, 2020. He was only 51 years old. Cecil was the Deputy Director and Director of Policy Initiatives at WE ACT, a West Harlem non-profit whose mission is to build healthy communities by ensuring that low-income communities of color participate meaningfully in the creation of environmental health and protection policies. Over his 26-year career at WE ACT, he helped develop and pass numerous bills in New York City and New York State, and managed WE ACT’s Washington, DC federal policy office.

West Harlem, New York, and the nation are so much better because of his selfless contributions of love, wisdom, and struggle. Rest in power Cecil.

To learn more about Cecil and his impact on the EJ community, click here.

Homenaje a Líderes Negros(as) en Justicia Ambiental:

La Encrucijada entre Raza y Justicia Ambiental

Febrero es Mes de la Historia Negra, una conmemoración nacional para celebrar y rendir homenaje a las innumerables aportaciones de las personas negras a nuestro país y al mundo. En honor a dicho mes, Environmental Health Coalition celebra a líderes negros(as) en el movimiento por la justicia ambiental y en nuestras comunidades. Para verdaderamente entender y apreciar a dichos(as) líderes, debemos primero reconocer la trágica historia de esclavitud, represión y racismo que ha sufrido – y con el que sigue lidiando a la fecha – el pueblo negro en nuestro país.

La lucha por la justicia ambiental es la lucha contra el racismo ambiental. Las injusticias que ha sufrido la gente de color, y en particular el pueblo Afroamericano, se documentaron en el emblemático informe Toxic Waste and Race in the United States (Residuos Tóxicos y Raza en los Estados Unidos), publicado por la Iglesia Unida de Cristo en 1987. El informe arroja que la raza es el factor más importante, por encima del nivel de ingresos de una comunidad, para decidir la ubicación de instalaciones de residuos tóxicos.

A la fecha, las comunidades negras continúan cargando con volúmenes desproporcionados de la contaminación y sus devastadores impactos en la salud. Según la American Lung Association (Asociación Pulmonar de EE.UU.) “Estudios recientes han analizado la mortalidad entre la población derechohabiente de Medicaid e identificado que quienes viven en comunidades predominantemente negras o afroamericanas sufren un mayor riesgo de muerte prematura a causa de contaminación por partículas que quienes viven en comunidades predominantemente blancas”. Tal y como dejan muy en claro estos estudios, la justicia ambiental lucha por la justicia racial, y la lucha aún no termina.

Líderes negros(as) dieron vida al movimiento por la justicia ambiental y continúan al frente de la lucha. Es un honor destacar a tan solo unos(as) cuantos(as) de estos(as) apasionados(as) y eficaces líderes quienes nos inspiran a todos(as).

Vernice Miller-Travis

Vernice ha dedicado a su vida a la justicia ambiental durante más de treinta años. Es una de las más respetadas líderes del país en el tema de justicia ambiental y la interrelación entre derechos civiles y políticas ambientales. Fue coautora del emblemático informe “Residuos Tóxicos y Raza en los Estados Unidos”. En 1991, fue una de las delegadas invitadas a la Primera Cumbre Nacional de Liderazgo Ambiental del Pueblo de Color. Durante la Cumbre, fue parte de un pequeño comité de redacción que produjo los Principios de la Justicia Ambiental. Actualmente funge como Vicepresidenta Ejecutiva de Metropolitan Group, un despacho de servicios integrales creativos y estratégicos dedicado a avanzar la justicia social.

Vernice ha dedicado a su vida a la justicia ambiental durante más de treinta años. Es una de las más respetadas líderes del país en el tema de justicia ambiental y la interrelación entre derechos civiles y políticas ambientales. Fue coautora del emblemático informe “Residuos Tóxicos y Raza en los Estados Unidos”. En 1991, fue una de las delegadas invitadas a la Primera Cumbre Nacional de Liderazgo Ambiental del Pueblo de Color. Durante la Cumbre, fue parte de un pequeño comité de redacción que produjo los Principios de la Justicia Ambiental. Actualmente funge como Vicepresidenta Ejecutiva de Metropolitan Group, un despacho de servicios integrales creativos y estratégicos dedicado a avanzar la justicia social.

EHC tuvo la oportunidad de preguntarle a Vernice acerca del nexo entre la justicia ambiental y la justicia racial, y ella tuvo la amabilidad de proporcionarnos la siguiente sensata respuesta:

Desde los primeros momentos de organización y abogacía en nuestras comunidades locales, entendimos que las amenazas al medioambiente y la salud pública que enfrentábamos tenían sus raíces en el racismo sistémico.

Iniciamos luchando contra el racismo ambiental. Pero este abordaje incomodó enormemente a las personas a cargo de normas a nivel local, estatal federal y del condado, así a como representantes de la industria, cuando sugerimos que el racismo sistémico estaba inmerso en uso de suelo, zonificación, vivienda y agricultura industrial, y en los patrones de desarrollo de toma de decisiones. Estas decisiones se basaban en prácticas históricas de segregación racial y étnica.

Mucho antes de que se publicara Residuos Tóxicos y Raza en los Estados Unido, Raza y la Incidencia de Amenazas Ambientales o Dumping in Dixie (Descargando en Dixie), toda persona de color en los Estados Unidos sabía sin lugar a duda que donde vivíamos nosotros era profundamente distinto a donde vivía la gente blanca, incluso si vivíamos en la misma ciudad, poblado o condado. Nuestras escuelas y hospitales eran distintos, nuestros supermercados y farmacias eran distintas. Los sistemas de transporte eran distintos. Cuando digo distintos, me refiero a que eran profundamente desiguales. Pero, de manera más importante, el aire que respirábamos y el agua que tomábamos en la mayoría de los casos estaban llenos de contaminantes. Esto ocasionaba que nos enfermáramos más y que nuestra expectativa de vida fuera más corta.

La lucha por la Justicia Ambiental es hoy y siempre ha sido una lucha por justicia racial e igualdad de trato ante la ley.

Eric Wilson

Eric Wilson es Director de Recursos Humanos y Administración en Environmental Health Coalition. Eric cuenta con más de 20 años de experiencia administrativa y operativa en empresas con y sin fines de lucro. Su corazón late por la labor de justicia ambiental y social. A través de su liderazgo, Eric crea un entorno laboral de colaboración y apoyo en el que el personal de EHC puede desarrollarse para convertirse en paladines de la justicia ambiental y ayudar a residentes a materializar su poder innato en aras de crear barrios saludables y libres de contaminación.

Eric Wilson es Director de Recursos Humanos y Administración en Environmental Health Coalition. Eric cuenta con más de 20 años de experiencia administrativa y operativa en empresas con y sin fines de lucro. Su corazón late por la labor de justicia ambiental y social. A través de su liderazgo, Eric crea un entorno laboral de colaboración y apoyo en el que el personal de EHC puede desarrollarse para convertirse en paladines de la justicia ambiental y ayudar a residentes a materializar su poder innato en aras de crear barrios saludables y libres de contaminación.

Eric nos comparte, “Soy apasionado por la justicia ambiental y social por un incidente que me ocurrió cuando tenía como 14 [años]. Arrestaron a mi cuñado sin causa y lo golpearon muy fuerte porque conducía por una colonia donde no pertenecía. Estuvo hospitalizado varias semanas. Fue entonces que descubrí lo que significa ser negro en Estados Unidos, ya que mi padre me tuvo que explicar esta doble moral. Me enojó tanto que nunca he olvidado la experiencia, y desde entonces he tenido el deseo de luchar por lo correcto. Me apego fielmente a la cita del Dr. King:

‘Nuestras vidas empiezan a terminar el día que guardamos silencio ante las cosas que importan”. “La verdadera medida de un hombre no es su postura en circunstancias convenientes y cómodas, sino su postura en tiempos de retos y controversias”.

Dra. Roberta Alexander

Al haber sido Pantera Negra, Roberta ha dedicado su vida a justicia social, educación y enriquecimiento cultural. En su función como integrante de la Junta Directiva de 2012 a la fecha, Roberta ha ayudado a guiar a Environmental Health Coalition a través de más de una década de retos y triunfos en justicia ambiental. Fue docente en el Distrito Escolar de Universidades Técnicas de San Diego (San Diego Community College District) durante más de 35 años y, durante su cargo, fungió como Jefa del Departamento de Inglés Como Lengua Extranjera en Educación Continua dentro de la escuela para adultos Centre City, así como Jefa del Departamento de Inglés en San Diego City College.

Al haber sido Pantera Negra, Roberta ha dedicado su vida a justicia social, educación y enriquecimiento cultural. En su función como integrante de la Junta Directiva de 2012 a la fecha, Roberta ha ayudado a guiar a Environmental Health Coalition a través de más de una década de retos y triunfos en justicia ambiental. Fue docente en el Distrito Escolar de Universidades Técnicas de San Diego (San Diego Community College District) durante más de 35 años y, durante su cargo, fungió como Jefa del Departamento de Inglés Como Lengua Extranjera en Educación Continua dentro de la escuela para adultos Centre City, así como Jefa del Departamento de Inglés en San Diego City College.

Roberta nos comparte, “En los sesenta, viví en las llanuras de North Richmond junto a la refinería tóxica de Chevron, lugar en el que no por accidente gente de tez negra y café sigue constituyendo la gran mayoría de la población. Todos los días sin excepción, nuestros(as) hijos(as) siguen batallando por respirar entre vapores tóxicos en barrios como este. De hecho, aquí mismo en San Diego, en el resto del país y en otros en el extranjero contaminación atmosférica, plantas de residuos peligrosos, intoxicación por plomo, cambio climático y contaminación del agua afectan desproporcionadamente a gente pobre y de color.

George Floyd, en los momentos de su asesinato por una rodilla sobre su cuello lamentó, ‘no puedo respirar’. Nuestros(as) niños(as) usan las mismas tres palabras cuando sufren de un ataque de asma”.

Mustafa Santiago Ali

Mustafa es un líder de opinión y activista comprometido a luchar por la justicia ambiental y la equidad económica. Trabajó en la Agencia de Protección Ambiental de EE.UU. (EPA, por sus siglas en inglés) durante 24 años. En EPA, fungió como Subadministrador Asistente de Justicia Ambiental y como Asesor en Jefe en Materia de Justicia Ambiental y Revitalización de Comunidades. Durante su periodo con dicha dependencia, trabajó de manera transversal con otras dependencias federales para fortalecer políticas, programas e iniciativas de justicia ambiental. Además, dirigió el Grupo de Trabajo Interdependencia de Justicia Ambiental (Interagency Working Group on Environmental Justice, o EJIWG), integrado por 17 dependencias federales y oficinas de la Casa Blanca enfocadas a implementar estrategias integrales para abordar las problemáticas que enfrentan comunidades vulnerables. En 2017, renunció a su puesto en EPA para sumarse a la bancada Hip Hop y dirigir su cartera de trabajo en Justicia Ambiental y Revitalización de Comunidades.

Mustafa es un líder de opinión y activista comprometido a luchar por la justicia ambiental y la equidad económica. Trabajó en la Agencia de Protección Ambiental de EE.UU. (EPA, por sus siglas en inglés) durante 24 años. En EPA, fungió como Subadministrador Asistente de Justicia Ambiental y como Asesor en Jefe en Materia de Justicia Ambiental y Revitalización de Comunidades. Durante su periodo con dicha dependencia, trabajó de manera transversal con otras dependencias federales para fortalecer políticas, programas e iniciativas de justicia ambiental. Además, dirigió el Grupo de Trabajo Interdependencia de Justicia Ambiental (Interagency Working Group on Environmental Justice, o EJIWG), integrado por 17 dependencias federales y oficinas de la Casa Blanca enfocadas a implementar estrategias integrales para abordar las problemáticas que enfrentan comunidades vulnerables. En 2017, renunció a su puesto en EPA para sumarse a la bancada Hip Hop y dirigir su cartera de trabajo en Justicia Ambiental y Revitalización de Comunidades.

Por su labor vitalicia en pro de la justicia ambiental, EHC galardonó a Mustafa con el Premio Paladín de Justicia Ambiental en 2018. Durante la ceremonia de reconocimiento, dio un conmovedor discurso de aceptación que podrá encontrar en el siguiente enlace:

Cecil Corbin-Mark

La comunidad de justicia ambiental sufrió una gran pérdida al fallecer el activista de Harlem Corbin-Mark el 15 de octubre de 2020. Cecil fue Subdirector y Director de Iniciativas Políticas en WE ACT, una organización sin fines de lucro en West Harlem cuya misión es crear comunidades saludables mediante vigilar que comunidades de escasos recursos y de color tengan oportunidad de participar plenamente en la creación de políticas de salud y protección ambiental. Durante sus 26 años de trayectoria en WE ACT, colaboró en el desarrollo y la aprobación de un sinnúmero de proyectos de ley en la Ciudad de Nueva York y el Estado de Nueva York, y administró la oficina de políticas federales de WE ACT en Washington, D.C.

La comunidad de justicia ambiental sufrió una gran pérdida al fallecer el activista de Harlem Corbin-Mark el 15 de octubre de 2020. Cecil fue Subdirector y Director de Iniciativas Políticas en WE ACT, una organización sin fines de lucro en West Harlem cuya misión es crear comunidades saludables mediante vigilar que comunidades de escasos recursos y de color tengan oportunidad de participar plenamente en la creación de políticas de salud y protección ambiental. Durante sus 26 años de trayectoria en WE ACT, colaboró en el desarrollo y la aprobación de un sinnúmero de proyectos de ley en la Ciudad de Nueva York y el Estado de Nueva York, y administró la oficina de políticas federales de WE ACT en Washington, D.C.

West Harlem, Nueva York y el país están en mucho mejor situación gracias a sus generosas aportaciones de amor, sabiduría y lucha. Descansa en poder, Cecil.

Para conocer mayores detalles acerca de Cecil y su impacto en la comunidad de Justicia Ambiental, haga clic aquí..