Citizen's Petition to the NAFTA

Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC)

The CEC established a process for citizens of the NAFTA countries to file a petition against the government of any of the participating countries (the United States, Mexico and Canada) for failing to effectively enforce its environmental laws. EHC was one of the first to take advantage of this process in October 1998. A copy of our petition can be found at: http://www.cec.org/files/pdf/sem/98-7-SUB-OE.pdf

Information on submitting a citizen's petition is at: http://www.cec.org/citizen/guide_submit/index.cfm?varlan=english

CEC report NAFTA's Commission for Environmental Cooperation accepted [EHC and the Colonia Chilpancingo's Citizens' Submission Petition] in 1998 and released its [Metales y Derivados Final Factual Record] in 2002, confirming the community's concerns about high levels of toxics at the site.

http://www.cec.org/citizen/submissions/details/index.cfm?varlan=english&ID=67

Community/Government Agreements

The cleanup agreement, the agreement to establish the Working Group, and the agreement to finalize the cleanup project, signed in June and July 2004 and July 2008 respectively, are landmarks for environmental justice. These documents are only available in Spanish.

Selected Cleanup Process Documents

These documents record key moments in the struggle to clean up Metales y Derivados.

Foro sobre Metales y Derivados Historia y Lucha de la Colonia Chilpancingo. These documents are only available in Spanish.

Community Monitoring Record

Independent Consultant's Final Monitoring Report to the Community on the cleanup.

Media coverage

For links to many of the print articles written over the past ten years, click here.

Toxinformer articles

Environmental Health Coalition has documented many important moments in the struggle to clean up the toxic Metales y Derivados site in our newsletters.

The Great March for Border Environmental Justice: (August 2001)

Tijuana residents demand cleanup of

toxic site during 24-hour vigil: (April 2002)

Community pressure makes Mexican officials

take action at Metales site: (Click to View)

Chilpancingo residents present

community-based solution ... (July 2003, page 3

Update: Developments in the fight

to cleanup Metales y Derivados (October 2003, page 10)

EHC, Colectivo Chilpancingo form Metales cleanup... (April 2004, page 8)

Victory at last! Community celebrates... (August 2004, page 3)

Metales Y Derivados Update: (February 2006, page 9)

After More Than a Decade of Struggle,

Community Celebrates... (December 2007, page 4)

Articles and Books

The following writings put the struggle to clean up the toxic Metales y Derivados site in the worldwide context of environmental justice.

1. WARREN COUNTY'S LEGACY FOR MEXICO'S BORDER MAQUILADORAS, an article by Amelia Simpson, Director of the Border Environmental Justice Campaign, published by the Golden Gate University Environmental Law Journal, August 22, 2007.

2. In "Reading Chilpancingo," English teacher Linda Christensen describes a visit to Colonia Chilpancingo in Tijuana, Spring 2006.

3. The following books all contain chapters featuring the work of EHC and the Colectivo Chilpancingo.

Challenging the Chip

Ted Smith, David Sonnenfeld, David Naguib Pellow, eds., 2006, Temple University Press, includes a chapter discussing NAFTA, environmental justice and labor rights in the U.S.-Mexico border region written by Connie García and Amelia Simpson, Director of the Border Environmental Justice Campaign.

Out of the Sea and Into the Fire: Latin American-U.S. Immigration in the Global Age

Kari Lydersen, 2005, Common Courage Press, includes a chapter featuring EHC and the Colectivo's struggle to clean up Metales y Derivados and address the injustices of NAFTA in the border region.

Nafta from Below

Published by the Coalition for Justice in the Maquiladoras, includes a chapter on the Metales y Derivados struggle.

Video

See EHC communities mobilizing for environmental justice in the cross-border region.

1. Maquilápolis

2. Journey to Planet Earth "Future Conditional"

On October 11, 2011, EHC and our Mexican affiliate the Chilpancingo Collective for Environmental Justice marked an important victory in the bi-national campaign to restrict maquiladora truck traffic from

On October 11, 2011, EHC and our Mexican affiliate the Chilpancingo Collective for Environmental Justice marked an important victory in the bi-national campaign to restrict maquiladora truck traffic from

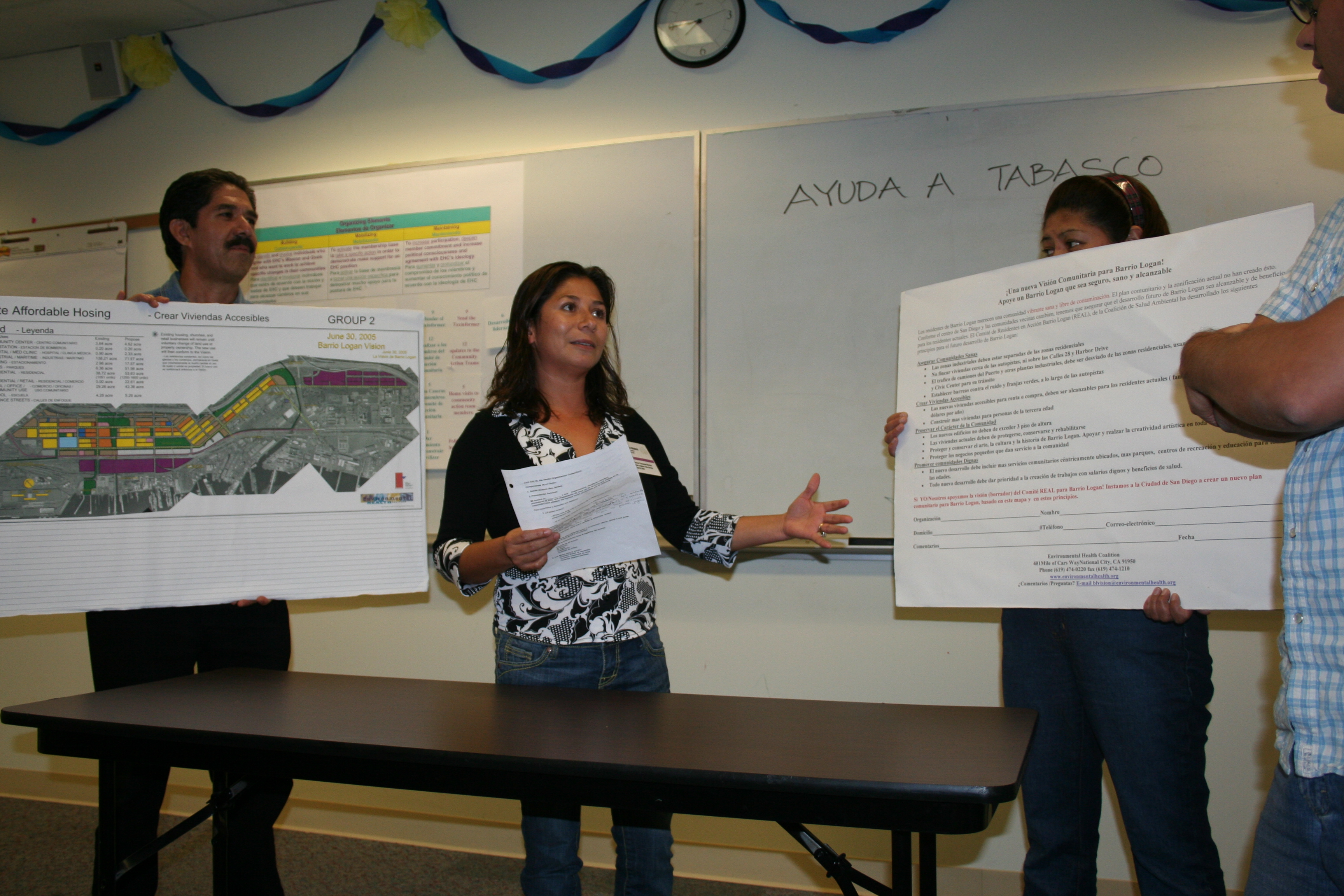

Authentic community involvement in every aspect of community planning and visioning leads to better outcomes that respect neighborhoods and their residents. EHC’s core strategies for all our efforts include community organizing and policy advocacy, which we combine with grassroots leadership development, research and communications to implement each strategic plan. To ensure that the community’s voice is heard, EHC employs the following tactics:

Authentic community involvement in every aspect of community planning and visioning leads to better outcomes that respect neighborhoods and their residents. EHC’s core strategies for all our efforts include community organizing and policy advocacy, which we combine with grassroots leadership development, research and communications to implement each strategic plan. To ensure that the community’s voice is heard, EHC employs the following tactics:

With corporate globalization, trade increased along the U.S.-Mexico border and so did pollution. However, trade agreements like NAFTA fail to hold polluting corporations responsible or to provide resources for environmental protection.

With corporate globalization, trade increased along the U.S.-Mexico border and so did pollution. However, trade agreements like NAFTA fail to hold polluting corporations responsible or to provide resources for environmental protection.