Under California law, all municipalities are required to complete General Plans which provide a blueprint and long range vision for cities. These can be very useful documents providing clear objectives (rollover comment: EHC successfully advocated for an Environmental Health and Justice element in the National City General Plan and a buffer zone between polluters and homes/schools in the Chula Vista General Plan – both firsts in the state), or can have lofty but vague goals. Community, area and specific plans are not required to be completed under state law but when executed are intended to apply General Plan standards to a specific geographic area and can enable communities to determine the density, building height, zoning and amenities for their neighborhood.

These plans have been the focus of EHC’s Community-Driven Planning efforts because they offer the opportunity for self-determination for residents and enable residents to be proactive rather than only reacting to inappropriate development proposals. The planning process is also the most holistic strategy for a community to engage in. It may allow residents, perhaps for the first time, to envision their community using their values and aspirations, not the developer’s or the city councilmember’s.

EHC is currently working on community-driven land-use planning in Barrio Logan, the Greater Logan area and City Heights in the City of San Diego, and in Old Town National City and West Chula Vista. Click on these links for the most current updates.

In each community, the underlying process is the same.

Building Community Power

Authentic community involvement in every aspect of community planning and visioning leads to better outcomes that respect neighborhoods and their residents. EHC’s core strategies, for all our efforts, are community organizing and policy advocacy, which we combine with grassroots leadership development, research and media communications to implement each strategic plan. To ensure that the community’s voice is heard, EHC employs the following tactics:

Community Action Teams: In each community, an EHC Community Action Team comprised of residents who are EHC leaders has been established. These leaders develop the community vision and priorities that direct EHC’s efforts. They serve as the spokespersons for the campaign meetings with elected officials and government agency representatives and on various planning committees established to oversee plan development.

José Medina, National City resident since 1969 and EHC leader, expressed his hopes for the Old Town National City Specific Plan when he said: “The plan will allow me to see the neighborhood change into something I remember when I was a boy, when a lot of residents were connecting with each other. In the mid-80s it changed for the worse – I saw houses flattened and autobody shops moved in.”

Leadership Training—Salud Ambiental Líderes Tomando Acción -- SALTA (Environmental Health, Leaders Taking Action): All EHC leaders complete an eight session Core SALTA training program providing them with skills and knowledge to become effective advocates and community organizers. A five session mini-SALTA focusing on land use also provides training on redevelopment, zoning, and affordable housing, plus air quality, contaminated site clean-up, reducing industrial pollution, and sustainable building, including green building materials and renewable energy options.

Community Surveying: EHC Leaders are committed to understanding the priorities of their neighbors, and representing those needs when developing EHC platforms and positions. Community surveying is often utilized as a method for collecting and documenting these needs. In Old Town National City, for example, leaders surveyed residents and found that development of affordable housing, relocation of autobody shops and changing zoning to prohibit incompatible mixed-use were the highest priorities by far, which were incorporated into the community plan.

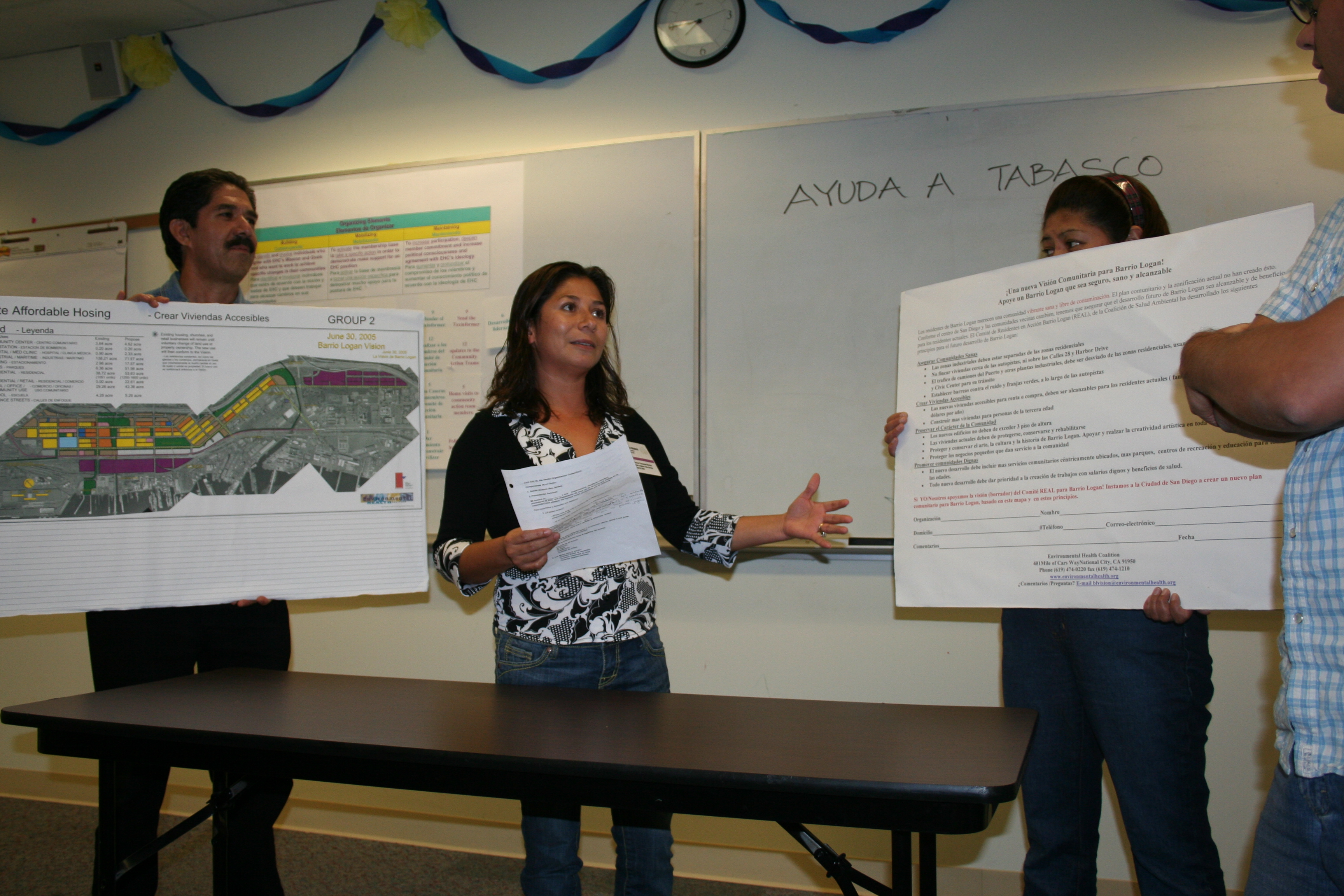

Community Visioning: Once aware of the impact and importance of community planning EHC leaders in both Barrio Logan and Old Town National City elected to develop their own neighborhood vision. EHC raised funds to employ a land use planning firm which, working with residents, developed detailed plans including zoning changes, volume and affordability levels of new housing units, identification of industries for relocation, park acreage, school requirements and more.

Barrio Logan’s community plan—one of the City of San Diego’s oldest—has not been updated since 1978. After years of promises and delays, residents took planning into their own hands. The result was the Barrio Logan Vision, now endorsed by over 1000 area residents, 28 community organizations and 16 local businesses. EHC then secured $1.5 million from a neighboring downtown development agency to update and revise the official Barrio Logan Community Plan, a process starting in early 2008. EHC is advocating for the community plan update to be consistent with the Barrio Logan Vision.

Hilda Valenzuela, EHC leader and Barrio Logan resident, expressed her excitement about the start of the planning process: “I hope with the Community Plan Update process we can resolve the problems sooner – improve affordable housing, have a healthier environment for children and a better place to live.”

Ensure Healthy Neighborhoods

For many years, EHC has promoted pollution prevention and the precautionary principle as the best solution to preventing toxic exposure for community residents and workers. Significant changes to these industrial practices are critical for safety but can take many years to accomplish. Communities subjected to toxic exposure due to discriminatory zoning need to take action to protect themselves and create separation between residential and industrial uses.

Buffer Zones

To accomplish this, EHC proposed the Toxic-Free Neighborhoods Ordinance in the City of San Diego in 1990, which would have required a buffer between industries using or emitting hazardous materials and residences, schools, and day care centers. Local polluters spent thousands of dollars lobbying against the ordinance and were ultimately successful in defeating it.

Without an ordinance EHC targeted polluters that chronically violated the law. Master Plating fit the bill with over 150 violations on the books. Community organizing efforts compelled the California Air Resources Board (CARB) and local government to take action resulting in Master Plating’s shutdown in 2002. CARB’s monitoring revealed a cancer risk four times higher than a ‘typical urban area’ due to hexavalent chromium emissions. As a result of this local action, CARB developed the Air Quality and Land Use Handbook in 2005 which recommended buffers for many polluters for the first time in state or local regulatory history. The recommended buffer for chrome platers is 1000 feet. The distance between Master Plating and the house next door was 4 feet! The guidance document also recommends separation of housing and major roadways which is often difficult given that ‘transit-oriented development’ may encourage development very near freeways.

Elvia Martinez, Master Plating’s next door neighbor and EHC leader, said: “This is the way it’s supposed to work…when a community works together to make its neighborhood a better place to live.”

Zoning

Community plans can include zoning ordinances that determine where industrial, commercial and residential areas will be located. Barrio Logan and Old Town National City are plagued with ‘mixed-use’ zoning that allows all three uses to be in the same area. EHC is seeking specific zoning designations that separate industrial areas from residential areas in the new community plans, and removal of mixed-use zoning.

Polluter Relocation and Removal

Rules that prohibit new sensitive uses near pollution sources are important, but in order for residential neighborhoods to truly be restored and healthy, polluters adjacent to homes and schools must be removed or relocated. EHC has pursued a few tactics to accomplish this. In National City, the City Council adopted an amortization ordinance that will phase out industries currently allowed to operate near sensitive uses, which sets up a process for relocation of prioritized industries when the amortization period is triggered.

Authentic community involvement in every aspect of community planning and visioning leads to better outcomes that respect neighborhoods and their residents. EHC’s core strategies for all our efforts include community organizing and policy advocacy, which we combine with grassroots leadership development, research and communications to implement each strategic plan. To ensure that the community’s voice is heard, EHC employs the following tactics:

Authentic community involvement in every aspect of community planning and visioning leads to better outcomes that respect neighborhoods and their residents. EHC’s core strategies for all our efforts include community organizing and policy advocacy, which we combine with grassroots leadership development, research and communications to implement each strategic plan. To ensure that the community’s voice is heard, EHC employs the following tactics: Con la globalización corporativa, el comercio y la contaminación han aumentado a lo largo de la frontera de Estados Unidos y México. Tratados como el TLCAN fallan en responsabilizar a las corporaciones contaminadoras o en proporcionar recursos para la protección ambiental.

Con la globalización corporativa, el comercio y la contaminación han aumentado a lo largo de la frontera de Estados Unidos y México. Tratados como el TLCAN fallan en responsabilizar a las corporaciones contaminadoras o en proporcionar recursos para la protección ambiental.