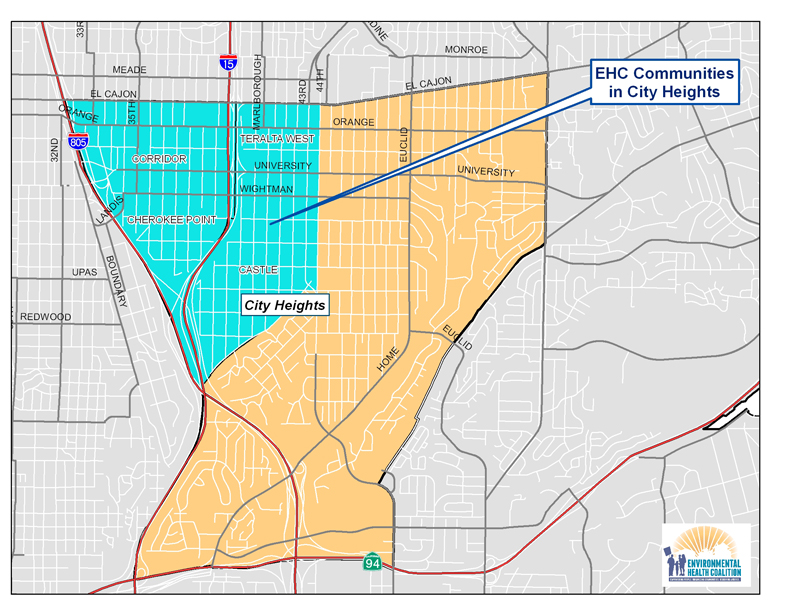

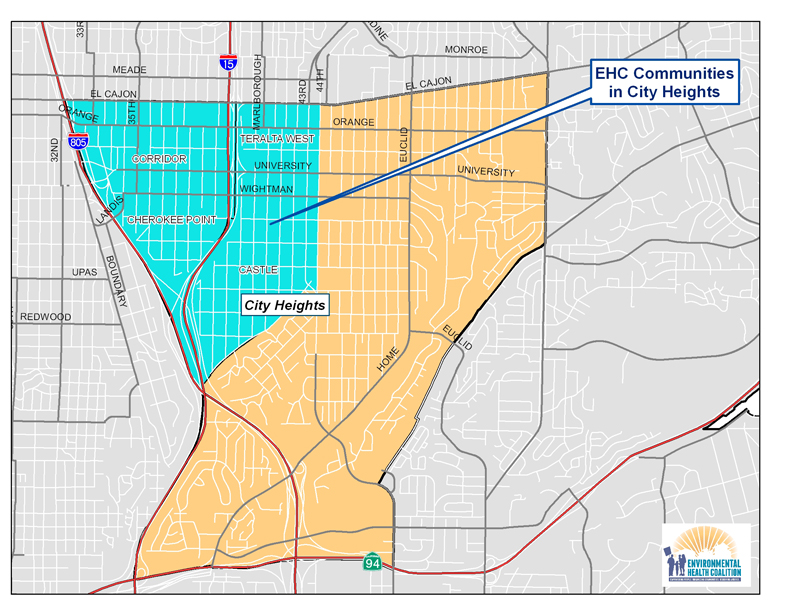

The current boundaries of City Heights were created by the 1998 Mid-City Communities Plan. Environmental Health Coalition works primarily in the Corridor, Teralta West, Cherokee Point and Castle neighborhoods, the neighborhoods most impacted by the freeways and the businesses along El Cajon Boulevard and University Avenue.

EHC's current efforts in City Heights

Community Planning – help community residents create a sustainable City Heights which is safe, healthy and affordable

Healthy Kids – reduce lead poisoning and asthma associated with poor housing and air pollution

Green Energy/Green Jobs – improve the housing stock through energy efficiency and installation of solar energy and create green jobs for community residents

History

In 1880, 240 acres of land were purchased by developers and named City Heights because of its 360 degree expansive views. The highest neighborhood was called Teralta. Although an electric trolley line connected the new community with downtown, growth was slow. The 1910 census showed only about 400 residents in City Heights.

Anticipation of the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exhibition in San Diego spurred growth, and by 1912 the 4,000 residents of City Heights voted to incorporate as a separate city called East San Diego. The city prided itself on its high moral character (no liquor stores, gambling or dance halls, no gun totting). A 1918 advertisement described City Heights as the home of the working men of San Diego; 8 out of 10 families owned their home. Thriving commercial development grew up along University Avenue and El Cajon Boulevard.

Soon the new city experienced problems: unavailability of a reliable supply of water; the trolley line operators threatened to discontinue service; the City of San Diego decided to greatly increase the cost for providing high school education for East San Diegans. In 1923, residents voted to become part of San Diego and this was finalized in 1924.

Zoning problems

City Heights continued to grow and prosper as a mostly white, middle class community until the College Grove shopping mall was completed in 1959. This began a rapid decline in business along University Avenue and El Cajon Boulevard, and failing business owners believed they could stave off bankruptcy by increasing the population density. The 1965 Mid-City Development Plan rezoned most of the area for multi-family dwelling units. Developers began tearing down single-family homes and putting up small, cheaply constructed apartment buildings known as "six-packs." In 1950, only 9% of housing in City Heights was multi-family units; by 1970 it was 31%; it is currently more than 60%.

As the housing density increased, the demographics shifted. Following the end of the Vietnam War in 1974 City Heights became home to many Southeast Asian refugees. This was followed by waves of other refugees fleeing violence in their homelands: Ethnic Albanians from Kosovo, Central Americans, East Africans, and Kurds. African-Americans and Latinos also moved to City Heights as rents in other parts of the City escalated, often due to gentrification. More than 30 languages and 80 dialects are now spoken in City Heights.

The 1970s and 80s saw sharp increases in crime, and the 1984 Mid-City Community Plan identified the increased multi-family residential housing with reduced resident ownership and deterioration of residential housing stock as major problems. In 1990, crime was so bad that the City declared a State of Emergency in City Heights.

Highway related problems

In 1932, City Heights welcomed the construction of the Fairmount/Murphy Canyon highway that connected communities to the north and south of Mission Valley, and extended all the way to Mexico. Interstate 805 was also seen as a boon to community access when it was built in the 1960s.

But the planned expansion of Interstate 15 that had been contemplated since the late 1950s was another issue. There were several starts and stops in the 1970s and CalTrans purchased hundreds of homes in anticipation of constructions. Instead of tearing them down, the houses were boarded up and became hangouts for drug users and prostitution.

Rebuilding

Several community non-profit groups formed in response to the decline in City Heights including the City Heights Community Development Corporation in 1981 and Mid-City Community Advocacy Network (Mid-City CAN) in the late 1980s. The CHCDC worked with residents in 1991 to develop a vision for the I-15 corridor – they supported a covered freeway to prevent neighborhoods from being torn apart and the loss of a significant area of land. As one resident said, she didn't want "a divisive slash through my community, a hole with cars in it." Covering the entire portion of I-15 through City Heights proved to be cost prohibitive. When I-15 was completed in 1999 only University Avenue and El Cajon Boulevard were widened over the freeway to accommodate bus stops and a park was built over the freeway between Orange and Polk Avenues close to Central Elementary School.

When the last supermarket serving City Heights announced in 1994 that it was leaving, Philanthropist Sol Price became involved. The City Heights Initiative was formed between Price Charities and public agencies and non-profit organizations. A new library/recreation/educational complex was built, along with a six story office building, hundreds of affordable housing units and La Maestra Community Health Clinic (a Gold Medal LEED certified building).

In 2010 The California Endowment included City Heights in its Building Healthy Communities initiative. The local collaboration is led by Mid-City CAN; EHC leads the Built Environment team that includes City Heights Community Development Corporation, Proyecto Casas Saludadbles, and the International Rescue Committee.

Environmental Racism

Environmental racism is not easily defined but easy to recognize; it is the cumulative impacts of environmental, social, political and economic vulnerabilities that affect the quality of life of a community.

Demographics

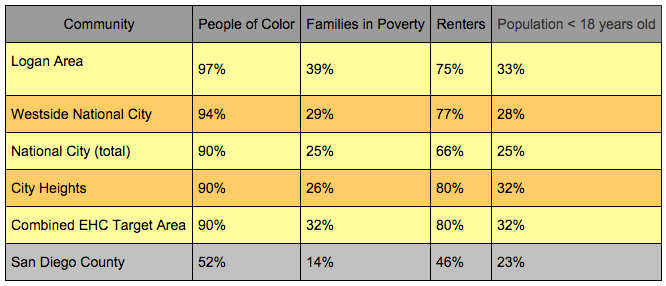

| Area |

2010 Population |

Non-White |

Under 18 |

18 and Older |

Families in Poverty |

Renter Households |

| City Heights |

18,482 |

90% |

32% |

68% |

32% |

87% |

Pollution Burden

City Heights has never had much industrial activity. Almost all of the Hazardous Materials Management and Air permits are for auto-related businesses and other small facilities that line much of University Avenue and El Cajon Blvd. Its pollution burden comes from its proximity to the freeways and the deteriorated quality of its housing.

Asthma hospitalization rates in 2009 for children ages 0-17 were 162/100,000 in City Heights compared to 107/100,000 for San Diego County as a whole. EPA Respiratory Risk data from 2009 show that City Heights residents experience a 4-5 times greater risk than a neighborhood considered "safe."

City Heights has been identified as a "hot spot" for childhood lead poisoning due to the age and poor condition of its housing and the large number of children under the age of 6. Most of City Heights original housing was built from 1910-1930 when levels of lead in paint were highest; the apartment boom of the 1960's and 1970's took place before lead was completely banned in household paint in 1978.

EHC's History/Successes in City Heights

- Blood Lead Level Testing. In October 2010 EHC sponsored a blood lead level testing at Cherokee Point Elementary School.

- Leader Development.

Relationships to other EHC Efforts

Regional Transportation Planning: Lack of adequate public transportation, congested surface streets, and increased freeway traffic are concerns for City Heights residents.

San Diego Bay: Chollas Creek runs through part of City Heights on its way to San Diego Bay.

Goods Movement (Port of San Diego and Border Ports of Entry): Interstate 805 is the major truck route for freight truck coming across the U.S./Mexico Border Port of Entry at Otay Mesa and from the Port District's Marine Terminal in National City. Interstate 15 was not intended as a major truck route, but is experiencing increased truck traffic.

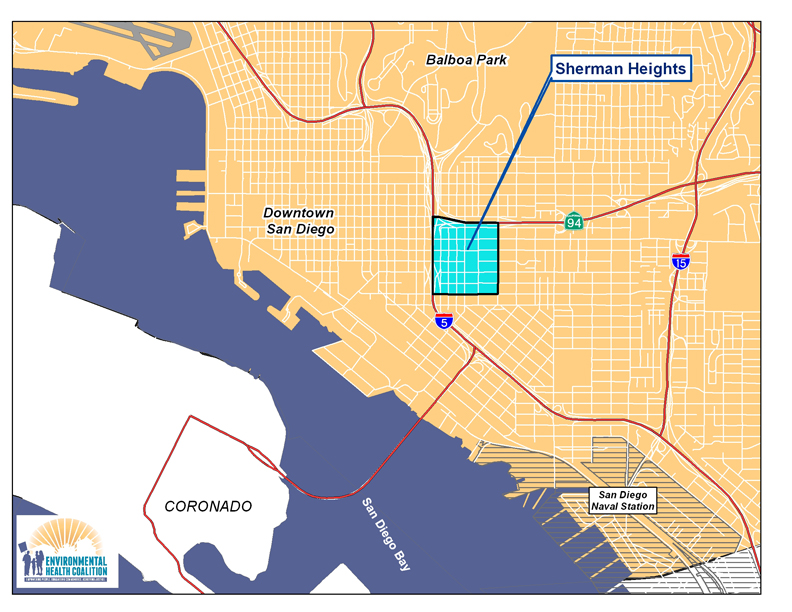

EHC's current efforts in Sherman Heights

EHC's current efforts in Sherman Heights

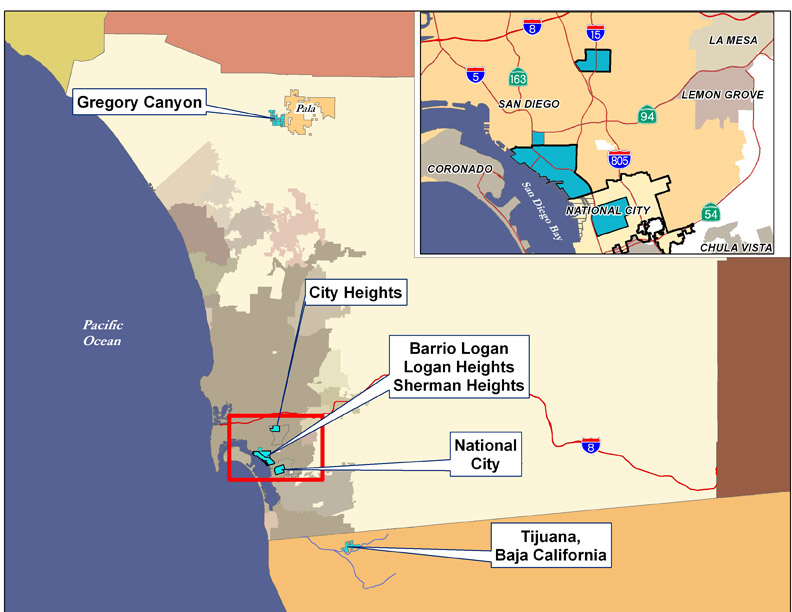

Environmental Health Coalition has opposed the construction of Gregory Canyon landfill for over a decade.

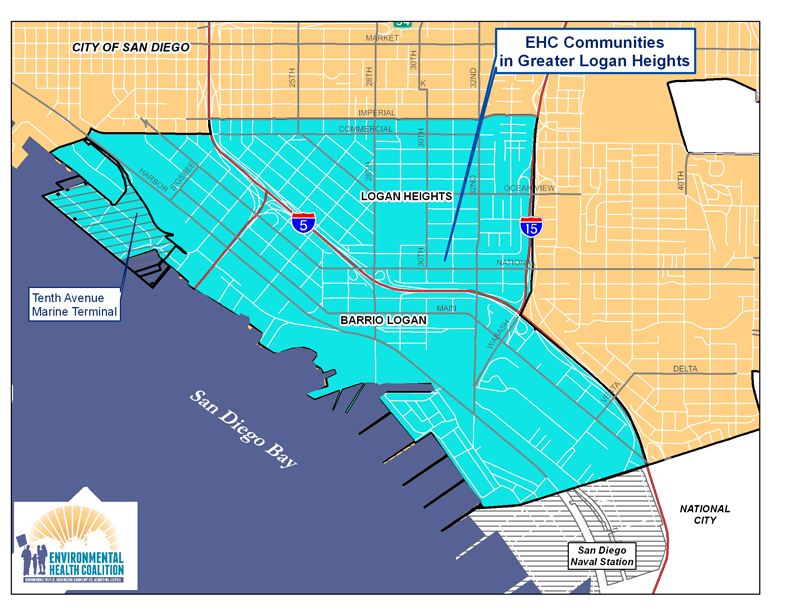

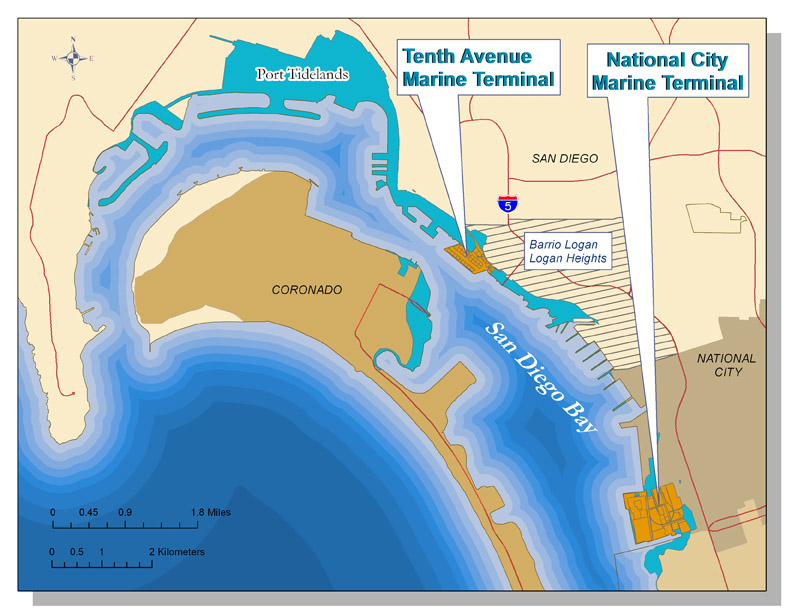

Environmental Health Coalition has opposed the construction of Gregory Canyon landfill for over a decade. The San Diego Unified Port District maintains two marine terminals: the 140 acre National City Marine Terminal and the 96 acre Tenth Avenue Marine Terminal in Barrio Logan. These terminals handle a variety of products including fruit, automobiles, lumber, and windmill components.

The San Diego Unified Port District maintains two marine terminals: the 140 acre National City Marine Terminal and the 96 acre Tenth Avenue Marine Terminal in Barrio Logan. These terminals handle a variety of products including fruit, automobiles, lumber, and windmill components.

From 1960 until decommissioned in 2010, the South Bay Power Plant’s four generators polluted South San Diego Bay and emitted tons of toxic and greenhouse gases.

From 1960 until decommissioned in 2010, the South Bay Power Plant’s four generators polluted South San Diego Bay and emitted tons of toxic and greenhouse gases. The US military is a major force in

The US military is a major force in  Environmental Health Coalition is a member of the California Environmental Justice Alliance. The other members are:

Environmental Health Coalition is a member of the California Environmental Justice Alliance. The other members are:

Protect your Child - Buy these Certified Lead-Free Candies

Protect your Child - Buy these Certified Lead-Free Candies

Common factors that contributed to the decline of each neighborhood include:

Common factors that contributed to the decline of each neighborhood include:

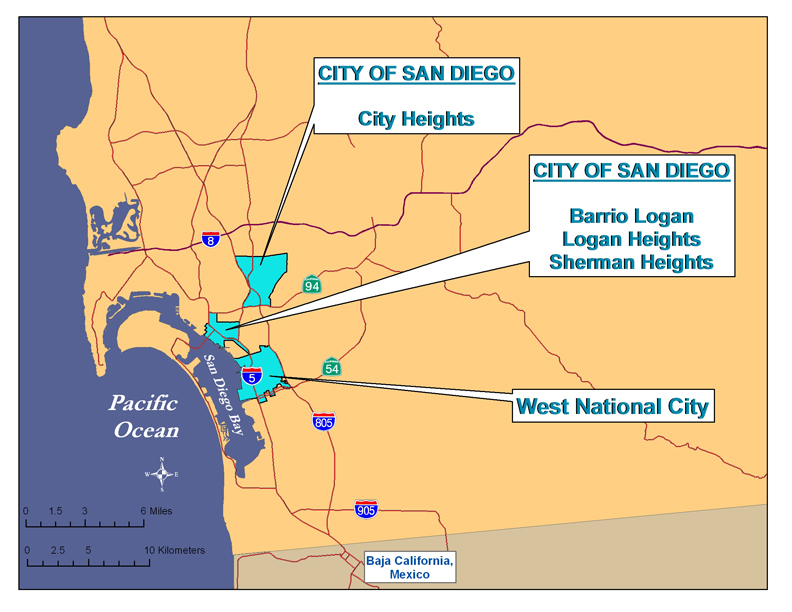

Environmental Health Coalition's efforts are mainly focused in communities but a glance at our

Environmental Health Coalition's efforts are mainly focused in communities but a glance at our  The San Diego Unified Port District was created by state legislation in 1962 to promote commerce, navigation, recreation and fisheries for most of the tidelands in the five cities around

The San Diego Unified Port District was created by state legislation in 1962 to promote commerce, navigation, recreation and fisheries for most of the tidelands in the five cities around  History of San Diego Bay

History of San Diego Bay

Most of the land surrounding San Diego Bay is controlled by the San Diego Unified Port District or the U.S. military. The last remaining piece of privately owned bayfront property was 125 acres between the Sweetwater Marsh Unit of the San Diego National Wildlife Refuge and a marina/commercial development on Port controlled land to the South. When developers proposed dense commercial and residential development at this site, environmentalists and South Bay residents objected.

Most of the land surrounding San Diego Bay is controlled by the San Diego Unified Port District or the U.S. military. The last remaining piece of privately owned bayfront property was 125 acres between the Sweetwater Marsh Unit of the San Diego National Wildlife Refuge and a marina/commercial development on Port controlled land to the South. When developers proposed dense commercial and residential development at this site, environmentalists and South Bay residents objected. Environmental Health Coalition believes that the proper role of government is to protect human and environmental rights. In addition to working locally, we work at state and national levels to promote government policies and regulations that protect human health and the environment. Many of these efforts are in cooperation with our allies in the

Environmental Health Coalition believes that the proper role of government is to protect human and environmental rights. In addition to working locally, we work at state and national levels to promote government policies and regulations that protect human health and the environment. Many of these efforts are in cooperation with our allies in the

NAFTA and the

NAFTA and the